My current novel in progress has plunged me deep into unfamiliar territory. Literally. The prairies and badlands of Southern Alberta. I'm an eastern city girl born and raised in Montreal and living most my adult life in Ottawa. I spent childhood summers in the Quebec's Eastern Townships (Three Pines territory) and my recent summers at my lakeside cottage in rural eastern Ontario. I did suffer through a couple of years of grad school in Toronto, but that was before the city got interesting. I travel extensively, and have made a point of trying to go to the far corners of the earth, but that's different from knowing the soul of a place.

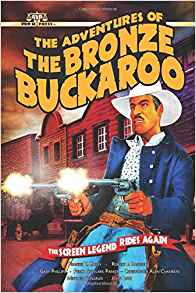

I wrote ten detective novels set in Ottawa, which I knew inside out, before deciding I wanted to explore farther afield. My choice of setting for my new Amanda Doucette series was very deliberate; I wanted to take the series across Canada and showcase the breadth and diversity of my magnificently complex country. Geographically, we go from craggy coastlines to vast inland lakes and forests to prairies and Rocky Mountains before reaching the Pacific. We go from the crowded, clamorous cities of southern Ontario to the windswept Arctic tundra of Nunavut. I wanted to bring readers along with me to visit all that.

It turns out to be a tall order. My novels are always deeply grounded in setting, which I try to capture vividly enough so the reader can see and feel it. Part of setting is the people, how they dress and talk, what they think and what they care about. I make a point of visiting the places and trying to do all the things Amanda would. Hence the winter camping in Quebec for The Trickster's Lullaby and the kayaking trip to Georgian Bay for Prisoners of Hope. Each book has given me lots of adventures, big and small, and it's been great fun as well as enlightening.

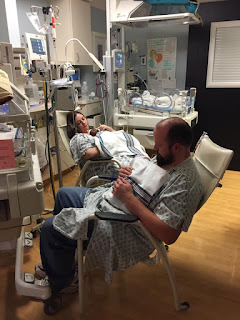

But in going west, I am starting to go farther from my roots and from the experiences that fashioned me. The Ancient Dead is set in Alberta, geographically and culturally a very different place. I have visited several times, most recently this past fall when I was specifically researching this book and trying to visit the exact locations and do the exact things Amanda would be doing. Now that I am back home writing the book, however, a thousand small questions keep cropping up. What time of the summer is the alfalfa crop harvested? What does the ICU at Foothills Medical Centre look like? How far north does the prairie rattlesnake extend? And what kind of curses would a farmer use? Writing each scene, I am either stopping to research the answers or putting in multiple question marks for a later time.

I do all this in the interests of authenticity, trust, and respect. Alberta readers will know if I get the alfalfa crop wrong. Calgarians will know I never set foot in the hospital there. Just as I hate it when cavalier writers get my home wrong, I don't want them turfing the book out because of a wrong note. If I have the audacity to venture into a place I don't know too well, I owe it to people to try my best to learn about it. As well, if readers know I got the small stuff wrong, how will they trust the truth of the bigger picture? Regional slang is particularly tricky. I've decided it's better not to use it than to use it wrong.

How on earth did we writers cope before the Internet? I wrote many books and short stories before the Internet was as rich and accessible as it is now, and I recall dragging home stacks of books from the library, making phone calls, and poring over maps and newspapers. I also remember just making stuff up. But the internet has put an extraordinary amount of detailed knowledge at our fingertips, and with that access has come an additional burden to try to get things right.

Bu the internet has its limits, especially when it comes to getting a feel for the culture. Reading local newspapers, biographical accounts, and blogs helps, but in the end I still have to make that extraordinary leap into my characters' heads and hope that, regardless of whether they grew up on the streets of Ottawa or on a ranch in Newell County, human concerns and desires – the stuff of crime fiction – are universal.

I wrote ten detective novels set in Ottawa, which I knew inside out, before deciding I wanted to explore farther afield. My choice of setting for my new Amanda Doucette series was very deliberate; I wanted to take the series across Canada and showcase the breadth and diversity of my magnificently complex country. Geographically, we go from craggy coastlines to vast inland lakes and forests to prairies and Rocky Mountains before reaching the Pacific. We go from the crowded, clamorous cities of southern Ontario to the windswept Arctic tundra of Nunavut. I wanted to bring readers along with me to visit all that.

It turns out to be a tall order. My novels are always deeply grounded in setting, which I try to capture vividly enough so the reader can see and feel it. Part of setting is the people, how they dress and talk, what they think and what they care about. I make a point of visiting the places and trying to do all the things Amanda would. Hence the winter camping in Quebec for The Trickster's Lullaby and the kayaking trip to Georgian Bay for Prisoners of Hope. Each book has given me lots of adventures, big and small, and it's been great fun as well as enlightening.

But in going west, I am starting to go farther from my roots and from the experiences that fashioned me. The Ancient Dead is set in Alberta, geographically and culturally a very different place. I have visited several times, most recently this past fall when I was specifically researching this book and trying to visit the exact locations and do the exact things Amanda would be doing. Now that I am back home writing the book, however, a thousand small questions keep cropping up. What time of the summer is the alfalfa crop harvested? What does the ICU at Foothills Medical Centre look like? How far north does the prairie rattlesnake extend? And what kind of curses would a farmer use? Writing each scene, I am either stopping to research the answers or putting in multiple question marks for a later time.

I do all this in the interests of authenticity, trust, and respect. Alberta readers will know if I get the alfalfa crop wrong. Calgarians will know I never set foot in the hospital there. Just as I hate it when cavalier writers get my home wrong, I don't want them turfing the book out because of a wrong note. If I have the audacity to venture into a place I don't know too well, I owe it to people to try my best to learn about it. As well, if readers know I got the small stuff wrong, how will they trust the truth of the bigger picture? Regional slang is particularly tricky. I've decided it's better not to use it than to use it wrong.

How on earth did we writers cope before the Internet? I wrote many books and short stories before the Internet was as rich and accessible as it is now, and I recall dragging home stacks of books from the library, making phone calls, and poring over maps and newspapers. I also remember just making stuff up. But the internet has put an extraordinary amount of detailed knowledge at our fingertips, and with that access has come an additional burden to try to get things right.

Bu the internet has its limits, especially when it comes to getting a feel for the culture. Reading local newspapers, biographical accounts, and blogs helps, but in the end I still have to make that extraordinary leap into my characters' heads and hope that, regardless of whether they grew up on the streets of Ottawa or on a ranch in Newell County, human concerns and desires – the stuff of crime fiction – are universal.